A Case for the Architecture of Attention

Loading the Elevenlabs Text to Speech AudioNative Player...

It is harder than ever to hear anything on purpose. Music follows us everywhere, dissolved into playlists calibrated for productivity, sleep, focus, or the gym. It fills retail spaces and hotel lobbies as a ubiquitous utility that exists primarily to modulate the mood of a room. Listening has become frictionless and solitary, functioning as a backdrop rather than a central event. We have gained convenience but lost the physical infrastructure designed for listening together. The shared experience of sound has been privatized, moving from the town square to the isolation of the noise-canceling headphone.

♪ Dive into the playlist. Listen along on: Apple Music & Spotify.

This loss is civic as much as it is aesthetic. The places we once relied on to practice being together without an agenda are thinning out. They have been replaced by environments optimized for throughput, extraction, and the rapid pace of digital transaction. Attention is now our most contested resource, constantly monetized by platforms that profit from interruption and fragmented focus. In that context, a third place that trains sustained attention is a counter-architecture. It is a room that makes a different kind of self possible by demanding that the listener remain present, still, and receptive.

The tradition of the Jazz Kissa, or jazu-kissaten, persists in the backstreets of Tokyo and Yokohama as a legacy of a movement that began in the late 1920s. These early ongaku kissa, or music cafés, established a culture of recorded sound during a broader fascination with Western music and modern ideas in Japan's urban centers. They offered an accessible sanctuary to experience the latest records at a time when private phonographs were a luxury and live performances were often constrained by law or expense. World War II severed that early scene with brutal finality. Many cafés were forced to close and wartime air raids destroyed rare, irreplaceable record libraries. This destruction created a profound cultural rupture. When peace returned, the movement entered a period of rebirth that felt inevitable because the hunger for the music had only intensified during the years of silence.

The mid-century boom of the Jazz Kissa emerged from material necessity and the friction of the postwar economy. In 1950s Japan, access to the global jazz canon was a privilege restricted by cost and geography. Imported LPs from labels like Blue Note, Verve, or Prestige were prohibitively expensive. They often cost more than a young fan could hope to amass in a personal collection over several months of labor. A high-fidelity audio system was a fantasy for a student living in a cramped, shared dormitory. The kissa functioned as a public library of sound where the rarity of the music was communalized. For the price of a single cup of coffee, the socio-economic barrier to high culture was flattened.

Future legends like pianist Toshiko Akiyoshi and saxophonist Sadao Watanabe learned their craft in these rooms. They spent hours hunched over tables and studied records they could never afford to own, utilizing the Master’s curated collection as their primary curriculum. The Master’s role was never passive. He presided over the turntable with a guru-like devotion, often delivering in-depth commentary to educate his clientele before dropping the needle. Regulars listened closely enough to take notes on the personnel, the specific recording dates, and the nuances of the arrangements. Magazines like Swing Journal provided listening guides that these proprietors used to evangelize the music. This human mediation offered a depth of context and a curated intent that no contemporary algorithm can replicate.

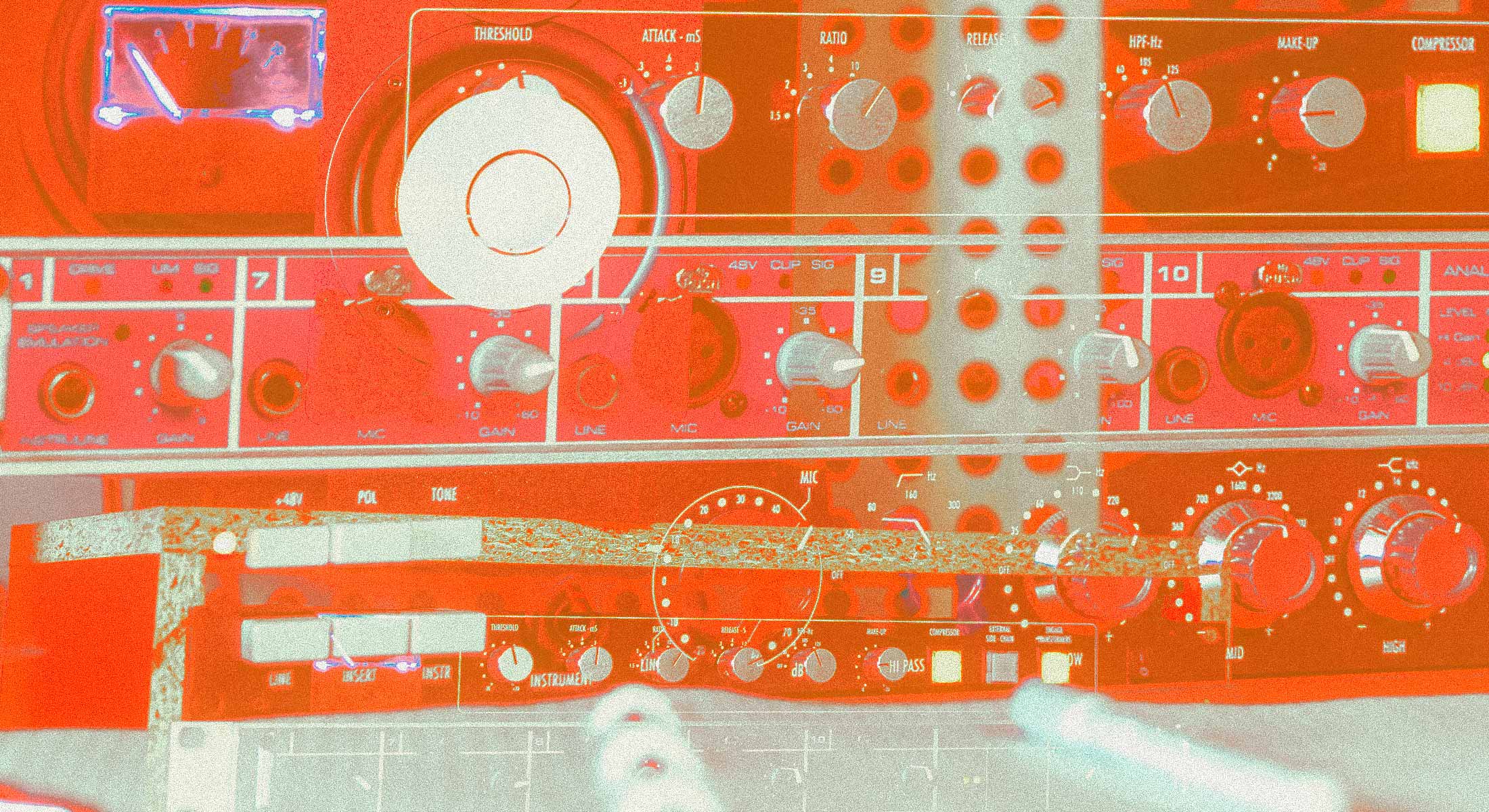

The physical reality of these spaces made listening unavoidable. The architecture was designed to dominate the room through a sensory overload of dark wood and vacuum tubes. A classic kissa was built around a shrine of massive vintage JBL or Altec Lansing cabinets. These were often custom-built into rooms barely larger than a living space and powered by glowing tube amplifiers that saturated the air with a specific, amber warmth. The audio gear was a point of immense pride and technical obsession. At Jazz Kissa Basie in Ichinoseki, founded by Shoji "Swifty" Sugawara, the sound was so visceral and the acoustics were so precise that Count Basie himself eventually made a pilgrimage there to hear the playback of his own recordings.

At Chigusa in Yokohama, which operated for nearly 90 years until its 2022 closure, the collection of 78rpm records and original turntables functioned as a pre-war time capsule for generations of listeners. Other venues like JAZZ BAR Eagle in Yotsuya curated libraries exceeding 20,000 records. This was not ambient sound intended for background chatter. It was chest-thumping and active. Every room was an instrument tuned with the devotion of a zealot to ensure that every crackle of the vinyl and every decay of a note carried its full emotional weight.

By the mid-1970s, the movement reached a national peak of approximately 600 cafés, with over 250 concentrated in Tokyo alone. This growth coincided with the student protest movement and a rise in free jazz experimentation. The clientele skewed bohemian and intellectual. These cafés often doubled as venues for political meetings and radical lectures by day and frenetic listening sessions by night. Silence in the kissa became a social contract that demanded a specific kind of presence. In hardcore environments, conversation was strictly prohibited. Signs firmly reminded patrons to Shizuka ni!, or to be quiet.

This mandate provided the essential mechanism for collective immersion. Silence served as a form of spiritual training and a rigorous socialization into the discipline of jazz appreciation. It was an art form to be analyzed, archived, and deeply felt. The hardcore jazz coffeehouses were not places at which to socialize in the traditional sense. They were pseudo-religious spaces where one was evangelized into a mental discipline. Camaraderie existed in the unspoken gestures, such as a shared nod when the needle dropped on a particularly luminous solo or a collective holding of breath as a phrase resolved.

What makes this powerful is that it restores a shared norm. Private listening can be intense, but it is self-governed because the listener can pause, skip, or scroll at will. A kissa turns attention into a public practice. The room holds the listener to their own intention, and the presence of others makes that intention legible. The constraint is the point of the experience. It is how a dispersed set of individuals becomes an audience. The Master drops the needle and the room enters a state of collective reception that is increasingly rare in a culture of fragmented consumption.

This is also why the kissa matters as a third place. It offers belonging without performance. You do not have to speak to participate, but you still feel the social fact of others beside you. In a culture where many public spaces demand either consumption or productivity, the jazz kissa models an alternative. It is a place where the primary transaction is attention itself. It is a sanctuary for those who seek to be socialized into a deeper engagement with art.

The decline of the Jazz Kissa in the late 20th century mirrors a broader cultural fragmentation toward the private sphere. Home stereos became affordable. The Walkman and the CD made music portable and individual. The need for a fixed site of concentrated listening diminished as a result. The availability of reissues and domestic pressings meant that the Master was no longer the sole gatekeeper of the archive. This era also saw an internal debate between purism and adaptation. Some owners attempted to survive by allowing quiet conversation, brightening the rooms, or shifting repertoire toward fusion and electric jazz. This tension highlighted the growing rift between the kissa’s foundational intent and the spread of jazz as decorative background music in hotels and retail chains. We traded communion for convenience.

Today, we exist in a paradox where we have unprecedented access to every recorded sound in history but almost no shared framework for experiencing it together. Even when we are physically near one another, many of our habits are designed for parallel solitude. The global resurgence of listening bars in London, New York, Los Angeles, and Seoul suggests a hunger for something different. This movement is also fueled by a new wave of jazz kissa tourism, where international music lovers seek out these hidden gems as a sort of pilgrim's journey. Younger successors and new proprietors are currently reviving the form by moving away from purely private consumption.

These new spaces require the kissa’s core intentionality to be successful. They must operate on the understanding that attention is a collective act and that a space can exist without demanding productivity or transaction. The system matters, but so do the rules, the lighting, the pacing, and the lack of screens. Without that architecture, listening becomes another aesthetic layer applied to a standard bar environment. The goal is to recreate a room where the point is to receive something fully, alongside others, without interruption.

The Jazz Kissa offered a room where someone with little money but deep curiosity could sit in the dark and hear something extraordinary. This experience reminded patrons that listening is participation rather than merely consumption. It is a recognition of shared time and shared vulnerability. This represents a functional cultural infrastructure that allowed curiosity to align with a shared presence. In an age of ambient distraction, reclaiming these spaces restores a specific dignity to collective attention. We should build them again.

The following recordings served as the curriculum for generations of listeners. They were selected by proprietors for their technical brilliance and their ability to command a room.

♪ Dive into the playlist. Listen along on: Apple Music & Spotify.

Moanin’ – Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers (1958)

A soulful hard bop anthem that was hugely popular in Japan and often spun in jazz kissas for its irresistible groove and Lee Morgan’s trumpet brilliance.

Autumn Leaves – Cannonball Adderley (feat. Miles Davis) (1958)

The modal take on this standard, famously opening Adderley’s Somethin’ Else, was a staple in many cafés. It provided a perfect blend of melancholy and swing for an autumn evening.

Take Five – The Dave Brubeck Quartet (1959)

This cool jazz classic, with its unusual 5/4 beat, became one of the most recognizable jazz tunes worldwide and was a frequent selection in the kissa circuit.

Take the 'A' Train – Duke Ellington Orchestra (1941)

A swing era standard that Japanese jazz fans adore. By the 1960s, Ellington’s live performances in Japan cemented it as a kissa favorite.

So What – Miles Davis (1959)

The opening track of Kind of Blue epitomizes the kind of high-art jazz the kissas treasured. It remains minimalist, modal, and deep on repeated listening.

Round Midnight – Thelonious Monk (1957)

Monk’s ballad is jazz at its most introspective. In a dimly lit kissa at midnight, this haunting melody cast a spell over everyone present.

The Girl from Ipanema – Stan Getz & João Gilberto (1964)

Jazz kissas played more than American bebop. Bossa nova and Latin jazz were in vogue, and this hit brought a mellow Brazilian vibe to many playlists.

Tokyo Blues – Horace Silver (1962)

Silver wrote this album after touring Japan. The bluesy swing with a faint Eastern flair made it a significant nod to the cross-cultural jazz connection.

Kyoto – Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers (1964)

Blakey recorded this propulsive tune as a tribute to Japan. Its presence honors the profound impact his tours had on the Japanese jazz movement.

My Favorite Things – John Coltrane (1961)

Coltrane’s hypnotic soprano sax interpretation was beloved by Japanese listeners. Its modal vamp could transport a kissa audience into a trance.

Giant Steps – John Coltrane (1960)

A showcase of virtuosity and a bebop Everest that aficionados loved to dissect. No serious jazz café would be without some Coltrane on the turntable.

Misty – Tsuyoshi Yamamoto Trio (1974)

This lush live rendition on the Three Blind Mice label became an audiophile favorite for its crystal-clear recording. It was often used to demo big JBL speakers.

Tokyo Dating – Sadao Watanabe (1965)

A breezy bop number by Japan’s premier alto saxophonist. It captures the cosmopolitan swing of 1960s Tokyo and represents homegrown talent.

Long Yellow Road – Toshiko Akiyoshi (1961/1975)

A groundbreaking Japanese pianist and composer, Akiyoshi wrote this as a lyrical tribute to her homeland. It was a point of pride in Japanese jazz circles.

Early Summer – Ryo Fukui (1976)

This gentle waltz by the self-taught Sapporo pianist has a cult following today. It is emblematic of the hidden gems discovered within the kissa.

Waltz for Debby – Bill Evans Trio (1961)

These live Village Vanguard recordings were popular for their intimacy and lyricism. This waltz could hush any room with its delicate beauty.

In a Sentimental Mood – Duke Ellington & John Coltrane (1963)

A meeting of two jazz giants that blends Ellington’s elegance with Coltrane’s soul. It became a late-night staple in many coffeehouses.

April in Paris – Count Basie Orchestra (1955)

The signature Basie tune is warm and grand. Given that Basie’s name graces Japan’s most famous kissa, this swinging classic is a requisite inclusion.

Someday My Prince Will Come – Miles Davis (1961)

The title track features a lyrical solo that many Japanese fans adored. Its blend of familiarity and sophistication made it accessible yet artful.

Blue Train – John Coltrane (1957)

A hard bop staple with a bluesy riff often heard echoing in jazz cafés. It exemplifies the driving, foot-tapping side of jazz that balanced out the ballads.

St. Thomas – Sonny Rollins (1956)

This calypso-infused romp was a hit in Japan and offered a change of pace in café sets through its cheerful tenor sax melody.

Bags' Groove – Miles Davis (feat. Milt Jackson & Thelonious Monk) (1954)

A mid-1950s classic jam session tune showcasing swing and blues feeling. Regulars cut their teeth on records featuring this all-star lineup.

Stolen Moments – Oliver Nelson (1961)

A cool, modal piece from The Blues and the Abstract Truth. Its spacious quality made it ideal for thoughtful listening and quintessential kissa material.

Now's the Time – Charlie Parker (1945)

Bebop remains foundational. Parker’s upbeat blues connected listeners to the roots of the genre and was often heard in the mix.

Peace – Horace Silver (1959)

This lyrical ballad embodies the reflective, spiritual side of jazz that Japanese audiences hold dear. It served as a perfect final song as the Master dimmed the lights.

This loss is civic as much as it is aesthetic. The places we once relied on to practice being together without an agenda are thinning out. They have been replaced by environments optimized for throughput, extraction, and the rapid pace of digital transaction. Attention is now our most contested resource, constantly monetized by platforms that profit from interruption and fragmented focus. In that context, a third place that trains sustained attention is a counter-architecture. It is a room that makes a different kind of self possible by demanding that the listener remain present, still, and receptive.

The tradition of the Jazz Kissa, or jazu-kissaten, persists in the backstreets of Tokyo and Yokohama as a legacy of a movement that began in the late 1920s. These early ongaku kissa, or music cafés, established a culture of recorded sound during a broader fascination with Western music and modern ideas in Japan's urban centers. They offered an accessible sanctuary to experience the latest records at a time when private phonographs were a luxury and live performances were often constrained by law or expense. World War II severed that early scene with brutal finality. Many cafés were forced to close and wartime air raids destroyed rare, irreplaceable record libraries. This destruction created a profound cultural rupture. When peace returned, the movement entered a period of rebirth that felt inevitable because the hunger for the music had only intensified during the years of silence.

The mid-century boom of the Jazz Kissa emerged from material necessity and the friction of the postwar economy. In 1950s Japan, access to the global jazz canon was a privilege restricted by cost and geography. Imported LPs from labels like Blue Note, Verve, or Prestige were prohibitively expensive. They often cost more than a young fan could hope to amass in a personal collection over several months of labor. A high-fidelity audio system was a fantasy for a student living in a cramped, shared dormitory. The kissa functioned as a public library of sound where the rarity of the music was communalized. For the price of a single cup of coffee, the socio-economic barrier to high culture was flattened.

Future legends like pianist Toshiko Akiyoshi and saxophonist Sadao Watanabe learned their craft in these rooms. They spent hours hunched over tables and studied records they could never afford to own, utilizing the Master’s curated collection as their primary curriculum. The Master’s role was never passive. He presided over the turntable with a guru-like devotion, often delivering in-depth commentary to educate his clientele before dropping the needle. Regulars listened closely enough to take notes on the personnel, the specific recording dates, and the nuances of the arrangements. Magazines like Swing Journal provided listening guides that these proprietors used to evangelize the music. This human mediation offered a depth of context and a curated intent that no contemporary algorithm can replicate.

The physical reality of these spaces made listening unavoidable. The architecture was designed to dominate the room through a sensory overload of dark wood and vacuum tubes. A classic kissa was built around a shrine of massive vintage JBL or Altec Lansing cabinets. These were often custom-built into rooms barely larger than a living space and powered by glowing tube amplifiers that saturated the air with a specific, amber warmth. The audio gear was a point of immense pride and technical obsession. At Jazz Kissa Basie in Ichinoseki, founded by Shoji "Swifty" Sugawara, the sound was so visceral and the acoustics were so precise that Count Basie himself eventually made a pilgrimage there to hear the playback of his own recordings.

At Chigusa in Yokohama, which operated for nearly 90 years until its 2022 closure, the collection of 78rpm records and original turntables functioned as a pre-war time capsule for generations of listeners. Other venues like JAZZ BAR Eagle in Yotsuya curated libraries exceeding 20,000 records. This was not ambient sound intended for background chatter. It was chest-thumping and active. Every room was an instrument tuned with the devotion of a zealot to ensure that every crackle of the vinyl and every decay of a note carried its full emotional weight.

By the mid-1970s, the movement reached a national peak of approximately 600 cafés, with over 250 concentrated in Tokyo alone. This growth coincided with the student protest movement and a rise in free jazz experimentation. The clientele skewed bohemian and intellectual. These cafés often doubled as venues for political meetings and radical lectures by day and frenetic listening sessions by night. Silence in the kissa became a social contract that demanded a specific kind of presence. In hardcore environments, conversation was strictly prohibited. Signs firmly reminded patrons to Shizuka ni!, or to be quiet.

This mandate provided the essential mechanism for collective immersion. Silence served as a form of spiritual training and a rigorous socialization into the discipline of jazz appreciation. It was an art form to be analyzed, archived, and deeply felt. The hardcore jazz coffeehouses were not places at which to socialize in the traditional sense. They were pseudo-religious spaces where one was evangelized into a mental discipline. Camaraderie existed in the unspoken gestures, such as a shared nod when the needle dropped on a particularly luminous solo or a collective holding of breath as a phrase resolved.

What makes this powerful is that it restores a shared norm. Private listening can be intense, but it is self-governed because the listener can pause, skip, or scroll at will. A kissa turns attention into a public practice. The room holds the listener to their own intention, and the presence of others makes that intention legible. The constraint is the point of the experience. It is how a dispersed set of individuals becomes an audience. The Master drops the needle and the room enters a state of collective reception that is increasingly rare in a culture of fragmented consumption.

This is also why the kissa matters as a third place. It offers belonging without performance. You do not have to speak to participate, but you still feel the social fact of others beside you. In a culture where many public spaces demand either consumption or productivity, the jazz kissa models an alternative. It is a place where the primary transaction is attention itself. It is a sanctuary for those who seek to be socialized into a deeper engagement with art.

The decline of the Jazz Kissa in the late 20th century mirrors a broader cultural fragmentation toward the private sphere. Home stereos became affordable. The Walkman and the CD made music portable and individual. The need for a fixed site of concentrated listening diminished as a result. The availability of reissues and domestic pressings meant that the Master was no longer the sole gatekeeper of the archive. This era also saw an internal debate between purism and adaptation. Some owners attempted to survive by allowing quiet conversation, brightening the rooms, or shifting repertoire toward fusion and electric jazz. This tension highlighted the growing rift between the kissa’s foundational intent and the spread of jazz as decorative background music in hotels and retail chains. We traded communion for convenience.

Today, we exist in a paradox where we have unprecedented access to every recorded sound in history but almost no shared framework for experiencing it together. Even when we are physically near one another, many of our habits are designed for parallel solitude. The global resurgence of listening bars in London, New York, Los Angeles, and Seoul suggests a hunger for something different. This movement is also fueled by a new wave of jazz kissa tourism, where international music lovers seek out these hidden gems as a sort of pilgrim's journey. Younger successors and new proprietors are currently reviving the form by moving away from purely private consumption.

These new spaces require the kissa’s core intentionality to be successful. They must operate on the understanding that attention is a collective act and that a space can exist without demanding productivity or transaction. The system matters, but so do the rules, the lighting, the pacing, and the lack of screens. Without that architecture, listening becomes another aesthetic layer applied to a standard bar environment. The goal is to recreate a room where the point is to receive something fully, alongside others, without interruption.

The Jazz Kissa offered a room where someone with little money but deep curiosity could sit in the dark and hear something extraordinary. This experience reminded patrons that listening is participation rather than merely consumption. It is a recognition of shared time and shared vulnerability. This represents a functional cultural infrastructure that allowed curiosity to align with a shared presence. In an age of ambient distraction, reclaiming these spaces restores a specific dignity to collective attention. We should build them again.

Essential Recordings of the Jazz Kissa

The following recordings served as the curriculum for generations of listeners. They were selected by proprietors for their technical brilliance and their ability to command a room.

Moanin’ – Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers (1958)

A soulful hard bop anthem that was hugely popular in Japan and often spun in jazz kissas for its irresistible groove and Lee Morgan’s trumpet brilliance.

Autumn Leaves – Cannonball Adderley (feat. Miles Davis) (1958)

The modal take on this standard, famously opening Adderley’s Somethin’ Else, was a staple in many cafés. It provided a perfect blend of melancholy and swing for an autumn evening.

Take Five – The Dave Brubeck Quartet (1959)

This cool jazz classic, with its unusual 5/4 beat, became one of the most recognizable jazz tunes worldwide and was a frequent selection in the kissa circuit.

Take the 'A' Train – Duke Ellington Orchestra (1941)

A swing era standard that Japanese jazz fans adore. By the 1960s, Ellington’s live performances in Japan cemented it as a kissa favorite.

So What – Miles Davis (1959)

The opening track of Kind of Blue epitomizes the kind of high-art jazz the kissas treasured. It remains minimalist, modal, and deep on repeated listening.

Round Midnight – Thelonious Monk (1957)

Monk’s ballad is jazz at its most introspective. In a dimly lit kissa at midnight, this haunting melody cast a spell over everyone present.

The Girl from Ipanema – Stan Getz & João Gilberto (1964)

Jazz kissas played more than American bebop. Bossa nova and Latin jazz were in vogue, and this hit brought a mellow Brazilian vibe to many playlists.

Tokyo Blues – Horace Silver (1962)

Silver wrote this album after touring Japan. The bluesy swing with a faint Eastern flair made it a significant nod to the cross-cultural jazz connection.

Kyoto – Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers (1964)

Blakey recorded this propulsive tune as a tribute to Japan. Its presence honors the profound impact his tours had on the Japanese jazz movement.

My Favorite Things – John Coltrane (1961)

Coltrane’s hypnotic soprano sax interpretation was beloved by Japanese listeners. Its modal vamp could transport a kissa audience into a trance.

Giant Steps – John Coltrane (1960)

A showcase of virtuosity and a bebop Everest that aficionados loved to dissect. No serious jazz café would be without some Coltrane on the turntable.

Misty – Tsuyoshi Yamamoto Trio (1974)

This lush live rendition on the Three Blind Mice label became an audiophile favorite for its crystal-clear recording. It was often used to demo big JBL speakers.

Tokyo Dating – Sadao Watanabe (1965)

A breezy bop number by Japan’s premier alto saxophonist. It captures the cosmopolitan swing of 1960s Tokyo and represents homegrown talent.

Long Yellow Road – Toshiko Akiyoshi (1961/1975)

A groundbreaking Japanese pianist and composer, Akiyoshi wrote this as a lyrical tribute to her homeland. It was a point of pride in Japanese jazz circles.

Early Summer – Ryo Fukui (1976)

This gentle waltz by the self-taught Sapporo pianist has a cult following today. It is emblematic of the hidden gems discovered within the kissa.

Waltz for Debby – Bill Evans Trio (1961)

These live Village Vanguard recordings were popular for their intimacy and lyricism. This waltz could hush any room with its delicate beauty.

In a Sentimental Mood – Duke Ellington & John Coltrane (1963)

A meeting of two jazz giants that blends Ellington’s elegance with Coltrane’s soul. It became a late-night staple in many coffeehouses.

April in Paris – Count Basie Orchestra (1955)

The signature Basie tune is warm and grand. Given that Basie’s name graces Japan’s most famous kissa, this swinging classic is a requisite inclusion.

Someday My Prince Will Come – Miles Davis (1961)

The title track features a lyrical solo that many Japanese fans adored. Its blend of familiarity and sophistication made it accessible yet artful.

Blue Train – John Coltrane (1957)

A hard bop staple with a bluesy riff often heard echoing in jazz cafés. It exemplifies the driving, foot-tapping side of jazz that balanced out the ballads.

St. Thomas – Sonny Rollins (1956)

This calypso-infused romp was a hit in Japan and offered a change of pace in café sets through its cheerful tenor sax melody.

Bags' Groove – Miles Davis (feat. Milt Jackson & Thelonious Monk) (1954)

A mid-1950s classic jam session tune showcasing swing and blues feeling. Regulars cut their teeth on records featuring this all-star lineup.

Stolen Moments – Oliver Nelson (1961)

A cool, modal piece from The Blues and the Abstract Truth. Its spacious quality made it ideal for thoughtful listening and quintessential kissa material.

Now's the Time – Charlie Parker (1945)

Bebop remains foundational. Parker’s upbeat blues connected listeners to the roots of the genre and was often heard in the mix.

Peace – Horace Silver (1959)

This lyrical ballad embodies the reflective, spiritual side of jazz that Japanese audiences hold dear. It served as a perfect final song as the Master dimmed the lights.

Join the Club

Follow the organizations you care about. Track and save events as they’re announced, and discover your next enriching experience on Ode.